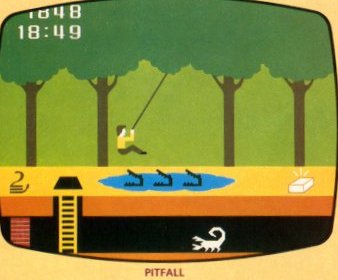

Humanity has always relied on our ability to make snap judgments of strangers so we could survive. Otherwise, there was always the chance of being caught unawares by a dangerous rival warrior masquerading as a peaceful trader. I haven’t heard of any recent Maryland tribal wars, but in hiring, we’re still stuck with the need to make snap judgments about people we don’t know particularly well. People evaluation is a task prone to pitfalls. We trust our instant assessments of candidates, yet research shows we are too often prone to error. And it’s far too easy to fall into crocodile-infested waters by making the wrong judgment call.

When interviewing, hiring executives usually place huge emphasis on a candidate’s track record of achievement. But they often overlook the context of that achievement. In Why Unqualified Candidates Get Hired Anyway, article writer Anna Secino paints a picture of “businesses repeatedly promoting or hiring less-qualified managers who benefit simply by being associated with a high-growth group.” A Harvard Business School study looks into whether hiring managers are just as prone to what psychologists call the “fundamental attribution error” – our tendency to attribute an individual’s success or failure solely to their inherent personal qualities, without considering the context in which they succeeded or failed.

The results of the HBS study suggest that “experts take high performance as evidence of high ability and do not sufficiently discount it by the ease with which that performance was achieved.” If someone works in a highly successful, well-operated company, and is highly successful as a result, we attribute their success to their innate ability. But if the exact same person works in a less successful company, fraught with employee tension and communication issues, and they failed at their task, we still attribute their failure to their innate ability to perform their job responsibilities effectively. We’ve discussed this dilemma before, and still love this quote from W. Edwards Deming: “A bad system will beat a good person every time.” Or as Warren Buffet put it, “When a manager with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for poor fundamental economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact.”

Understanding the environment that helped shape a candidate’s success or failure is one of the most important lessons to learn in hiring. So if you’re trying to hire someone, it’s a terrible idea to focus on their successes and assume that they will be equally successful in your environment. Consider the cautionary tale of Ron Johnson, who took over as CEO of J.C. Penney after huge successes with Target and Apple. He “helped make Target hip, pioneering partnerships with big-name designers like Michael Graves, and had then moved to Apple, where he orchestrated the creation of the Apple Store.” But fourteen months after the takeover:

J. C. Penney is America’s favorite cautionary tale. Customers have abandoned the store en masse: over the past year, revenues have fallen by twenty-five per cent, and Penney lost almost a billion dollars, half a billion of it in the final quarter alone. The company’s stock price, which jumped twenty-four per cent after Johnson announced his plans, has since fallen almost sixty per cent. Twenty-one thousand employees have lost their jobs. And Johnson has become the target of unrelenting criticism.

He was fired not long after. Of course, the criticism of Johnson focused on flaws that everyone seems to have considered in hindsight – he lacked CEO experience, never managed a turnaround, lacked middle-market management experience, etc. And not surprisingly, given the prevalence of the fundamental attribution error in human behavior, his failure was chalked up as a personal one, rather than one seen in the context of J.C. Penney’s difficulties. After all, “one study found that efforts at merely getting a money-losing retailer back to profitability succeed only thirty percent of the time.” It’s extraordinarily difficult for people to separate the context from the performance – a phenomenon Phil Rosenzweig calls “The Halo Effect.”

The key to great hiring is learning to spend less time on the irrelevant, superficial aspects of interviewing, and more time understanding the deeper elements of what will make someone successful. We recommend that you ask plenty of follow-up questions. Anyone can answer the question, “Tell me about your greatest achievement.” But the gold is how you follow up on their answer. “How did you achieve that? What roadblocks did you overcome? Who else was on your team? What was your role on the team? What decisions did you make in the face of uncertainty? What mistakes did you make? What did you learn from your mistakes? How did you measure your success?” That’s where the juice is. You will immediately see that the effective executive is much more concrete and tangible in their answers. More thoughtful. Their heads are full of metrics that they use to measure their own progress. They give ample credit to other people on their team and often sound quite humble about their own role.